What is Wove paper?

For some 500 years European Paper Makers, subject to the limitations of their papermaking mould (the piece of equipment used for making a sheet of paper) could only make Laid Paper, a sheet characterised by pronounced laid and chain wiremarks imprinted on the wet surface of the sheet by the wire cover of the mould. But in the mid-18th C. the Elder Whatman devised a mould which had a woven brass wire-cloth cover giving it the potential of producing a sheet unblemished by the furrows formerly found in laid paper; this was wove paper (or Papier Vélin in continental terminology). A perfect sheet of this kind would have many advantages for the Printer, Engraver and Artist. But Whatman was to find that just substituting one cover for another was a much more complicated process than he had originally thought. For one thing the wire-cloth used to make the wove had been woven on a textile loom resulting in surface imperfections which, in turn, were transferred to the paper. The new covers also created undesirable mould marks.

The first wove sheets would have offered no special advantage to a printer. Not only was the untreated paper quite rough but it bore significant corrugations derived from the cover's warp wires. It was probably not for another twenty years that the wire weavers created a loom to overcome this problem.

The first example of wove paper used in the West is to be found in Baskerville's printing of Virgil in 1757. For one reason or another the supply of wove paper was insufficient for the undertaking (28 sheets per volume). Whatman made-up the shortfall with a very unusual, but not unique, laid paper. In short the 1757 Virgil was printed on a mixture of wove and laid paper.

The involvement of Baskerville in this project is in a sense a red herring. The acclaim which his Virgil received was due to the glazed surface imposed by him equally on wove and laid paper alike after it had been printed on; together, of course, with admiration for his new type.

Whatman's task was quite a different one, how to improve the appearance of this new kind of paper; how to avoid ridges forming in the cover; and how to make the process more profitable. There were no guidelines to follow. The wire-weavers also had problems (Chapter II). Whatman and his mould-maker had only one course open to them, to experiment with "laid" moulds to eliminate disfiguring mould marks and waste.

Three experiments with laid paper were tried:

- A repeat of the very unusual laid cover used for the Virgil, to be used in this instance for the 1758 Octavo Milton [for all modules see Table 13(a), p.114].

- To extend the unusual modules as in (1) to their extremity for the laid paper to be used for the very rare 1758 Quarto Milton. For this Whatman produced a mould the likes of which had never been seen in Europe before (see below for more detail). This measure greatly improved the appearance of the laid paper and gave Whatman a vital clue for improving the wove. This version was rare because making further paper with this extreme mould was not a practical or economic proposition and the experiment was abandoned.

- The third experiment was a compromise, i.e. the laid module used for the 1759 Quarto Paradise Lost. By this time Whatman had planned to put the vital clue into practice. It led him to devise an altogether new type of mould and produce the near perfect sheets of "wove" paper found in the 1759 Quarto Paradise Regained.

Apropos of the extreme mould used in experiment 2, disregarding the infrastructure, which was also exceptional, one's attention is also drawn to the astonishing nature of the cover. In a laid cover chainwires are twisted between each laid wire to keep the laid wires in position. In a normal laid Foolscap mould there are about 5,000 twists per cover; in Whatman's 1758 Quarto crown mould there were approximately 25,000 twists per cover, an astonishing feat clearly done for a very special purpose.

At a later date Baskerville got another paper maker to imitate the special laid papers made for him by Whatman; but, in the end, his experiment proved no more successful.

Was it an invention of any importance or just a technological quirk ? If a quirk, the innovation would have passed away unnoticed within a generation. The opposite was to happen. Twenty-five years later (1780's) the manufacture of wove paper spread quickly to other paper mills in England; it was also being developed in France and America, all this taking place over a decade before a machine to replace making paper by hand was conceived. With the establishment of the papermachine (1807), the manufacture of paper on a wove wire base never looked back. Today more than 99% of the world's paper is made in this way.

At the time no one could have foreseen where the invention of wove paper was likely to lead. To understand the difficulties that confronted its inventor, we have to begin at the beginning and place ourselves in the pre-invention shoes of the paper maker to discover how he solved the problems without any precedents to guide him.

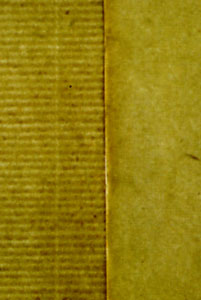

Laid and Wove paper side by side

Detail of Laid mould